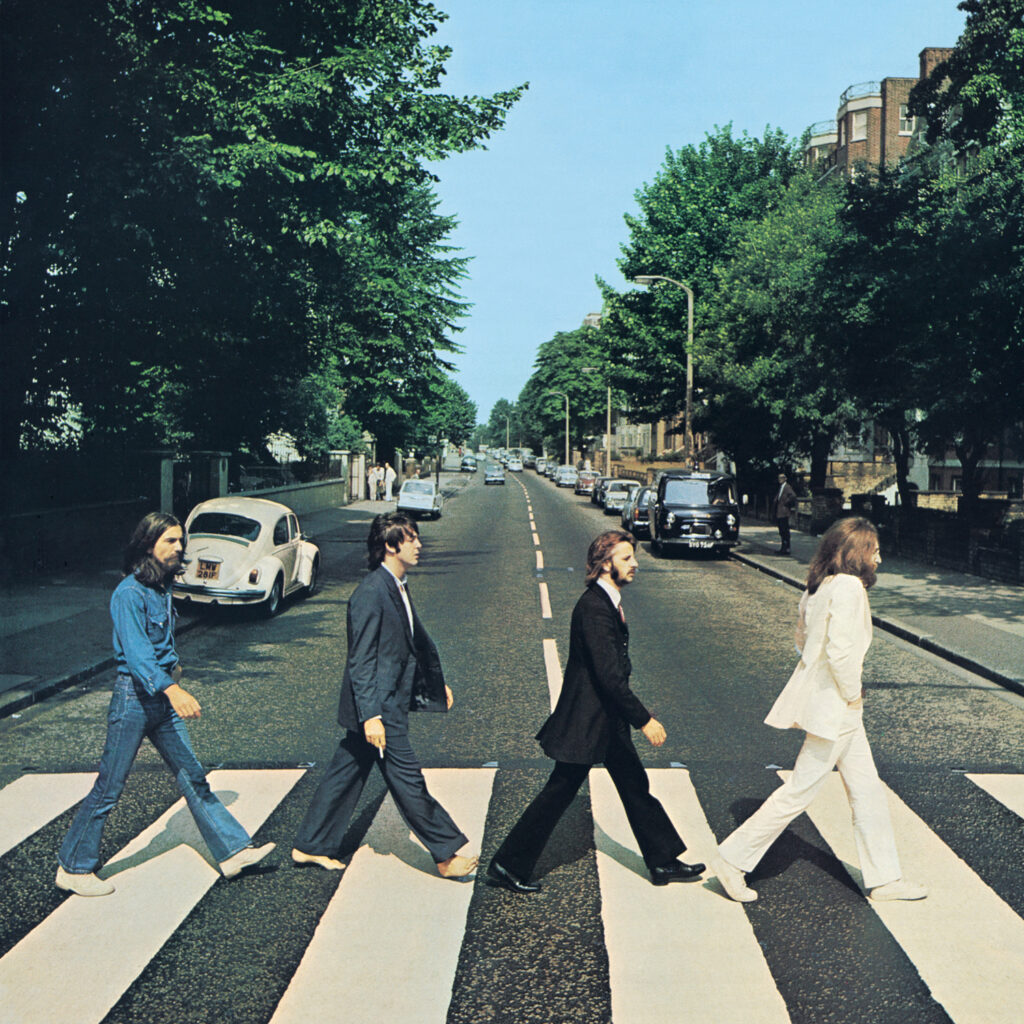

The Beatles, ‘Abbey Road,’ 1969

Here comes the sun, and I say

It’s alright

Abbey Road is The Beatles’ farewell—an elegy wrapped in harmony, its second side a breathtaking suite that feels like a final bow. Sensing the end, they reunited with George Martin, their longtime producer, and the result is nothing short of miraculous. When the scattered remnants of Let It Be were assembled the following spring, it marked the close of an era—an eight-year reign of innovation and influence that popular music may never see again.

Following The White Album, Paul McCartney decided to take the reigns as the group’s leader, sensing John Lennon was clearly losing interest in being a Beatle. He came up with a pretty solid idea: to rehearse a new batch of songs, perfect them, and realize them in a majestic live setting. McCartney thought it would be a good idea to film the rehearsals and the songwriting process for a documentary about this upcoming concert. Unfortunately, the constant infighting that marked the worst moments of The White Album sessions returned. The project, predictably, fell apart. After a few months away from it, McCartney and Lennon told George Martin they wanted to record one last album. He agreed. He also secured the services of engineer Geoff Emerick, a key move. When the group reconvened in April of 1969, they were refreshed and revitalized. The sessions were mostly tension-free, although Lennon was upset McCartney wouldn’t let him sing on Oh Darling!

Side One opens with Come Together, a slinky, enigmatic blues, Lennon’s cryptic murmurs floating over McCartney’s sinewy bass. Then comes Harrison’s Something—a love song so luminous even Sinatra called it the greatest ever penned. Here, the quiet Beatle emerges fully formed, no longer in their shadow. The album stumbles briefly with McCartney’s Maxwell’s Silver Hammer, a jaunty romp about a killer, and the retro pastiche of Oh! Darling. But Ringo’s Octopus’s Garden is pure delight, a sunlit cousin to Yellow Submarine. The side closes with I Want You (She’s So Heavy), an eight-minute blues monolith, Lennon’s desire distilled into a hypnotic groove. McCartney’s bass coils like smoke, the Moog synthesizer howls, and then—silence.

Yet it’s Side Two that cements Abbey Road’s legend. Not because every fragment is a masterpiece—many are slight—but because of how they intertwine, a mosaic of farewells. Harrison’s Here Comes the Sun is radiant, perhaps his finest moment. Lennon’s Because is celestial, its harmonies spiraling like starlight. Then, the medley begins: McCartney’s You Never Give Me Your Money shifts from wistful piano to jubilant release, a nod to their financial strife. What follows is a whirlwind—Lennon’s surreal Sun King, the sneering Mean Mr. Mustard, the bawdy Polythene Pam, all fleeting yet vivid. McCartney’s “She Came In Through the Bathroom Window” flickers by before the final, majestic trio: Golden Slumbers, tender as a lullaby; Carry That Weight, thunderous and weary; and The End, where Harrison, McCartney, and Lennon trade solos like parting gifts. Starr’s drum break—just ten seconds—is a bolt of lightning. And then, McCartney’s closing benediction: “And in the end / the love you take / is equal to the love you make.” Over twenty years later, during a sketch on Saturday Night Live, cast member Chris Farley asked McCartney if this was true. He said he thought so. Farley’s earnest, exuberant reaction to McCartney’s answer shows just how resonant and timeless this sentiment is. As if to shrug off the weight, they tack on Her Majesty, a cheeky postscript—and rock’s first hidden track.

Abbey Road is not the flawless masterpiece Revolver or The White Album is—its first side is strong but uneven. Yet its farewell resonance, that aching second side, and the sheer beauty of its craft make it unforgettable. Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band may wear the crown of “greatest album,” but Abbey Road outsells it, outlasts it. Even now, over fifty years on, it remains the only Beatles album in steady vinyl print, a testament to its undimmed magic. Some goodbyes are so perfect, they never really end.

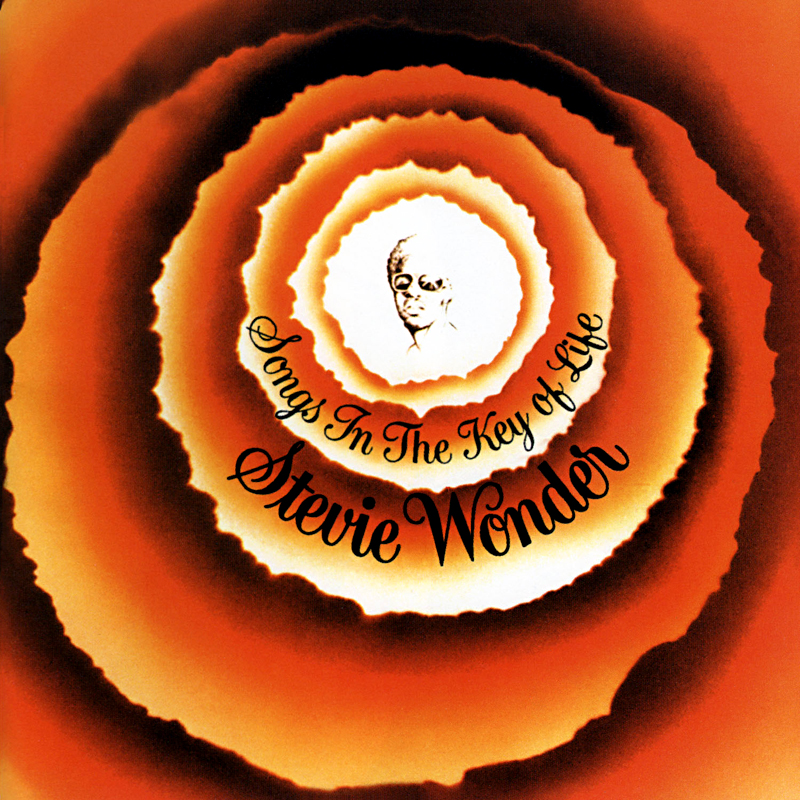

Stevie Wonder, ‘Songs In The Key Of Life,’ 1976

Songs in the Key of Life is a title that dares to encompass everything—every heartbeat, every tear, every fleeting joy and lingering sorrow. To name an album after life itself is an act of audacity, a gamble few artists could win without stumbling into pretension. But Stevie Wonder has never been like other artists. The world knew he was extraordinary from the moment a 13-year-old boy named Little Stevie unleashed the lightning strike of Fingertips Pt. 2, his first #1 hit. Through his teenage years, he sculpted Motown gold, mastering instruments as effortlessly as melodies. By 21, his contract expired, and Wonder—now a man, now a visionary—seized his destiny. He renegotiated for creative freedom, much like Marvin Gaye had, and what followed was a celestial run: five albums of soul alchemy, a streak so luminous it still dazzles. And at its zenith? Songs in the Key of Life.

This is an album that sprawls—nearly two hours of sound, yet not a second wasted. It shifts effortlessly between jazz-funk fire, velvety soul, and synth-kissed dreamscapes, each transition as natural as breath. Listening is like wandering through a garden where every bloom is impossibly vibrant: the dizzying rush of Contusion, where Wonder’s virtuosity dances with prog-funk precision; I Wish, a bass-thickened ode to childhood’s reckless joys; Sir Duke, a jubilant hymn to music itself, horns blazing like sunlight. Even at its most intricate, the complexity never overshadows the groove—it serves it, turning each song into pop perfection. Another Star is disco euphoria, la la la chants spiraling skyward, while As ascends into gospel transcendence, a love song that feels divine.

But Wonder’s genius lies in balance. The softer moments are just as breathtaking—Summer Soft begins as a whisper, swelling into a crescendo of aching beauty; Ordinary Pain and Joy Inside My Tears cradle heartache in lush arrangements. And then there’s Isn’t She Lovely, a lullaby so radiant it could melt stone. Even the experiments astonish: Have a Talk With God hums with otherworldly synth bass, while Ngiculela weaves Zulu, Spanish, and English into a tapestry of longing. Every track is a masterpiece. Choosing a favorite is futile.

Lyrically, the album fulfills its title’s promise—a prism refracting every hue of human emotion. There’s boundless joy (Isn’t She Lovely), devotion so vast it spans eternity (As), and heartache that still pulses with hope (Summer Soft). Yet Wonder also turns his gaze outward: Village Ghetto Land is a scathing portrait of systemic neglect, while Black Man reclaims history with funk-fueled pride. Even in sorrow, there’s warmth—“Love’s in Need of Love Today” pleads for tenderness in a wounded world. He doesn’t just sing about life; he captures it.

Upon release, the world recognized Songs in the Key of Life for what it was: an instant classic. It won Album of the Year (his third in a row) and became his only diamond record. It was the crown of his golden era—a streak that, inevitably, couldn’t last. The ’80s brought hits (some charming, some… less so), but nothing dims the incandescence of this album. Because here, Stevie didn’t just make music. He bottled life itself.