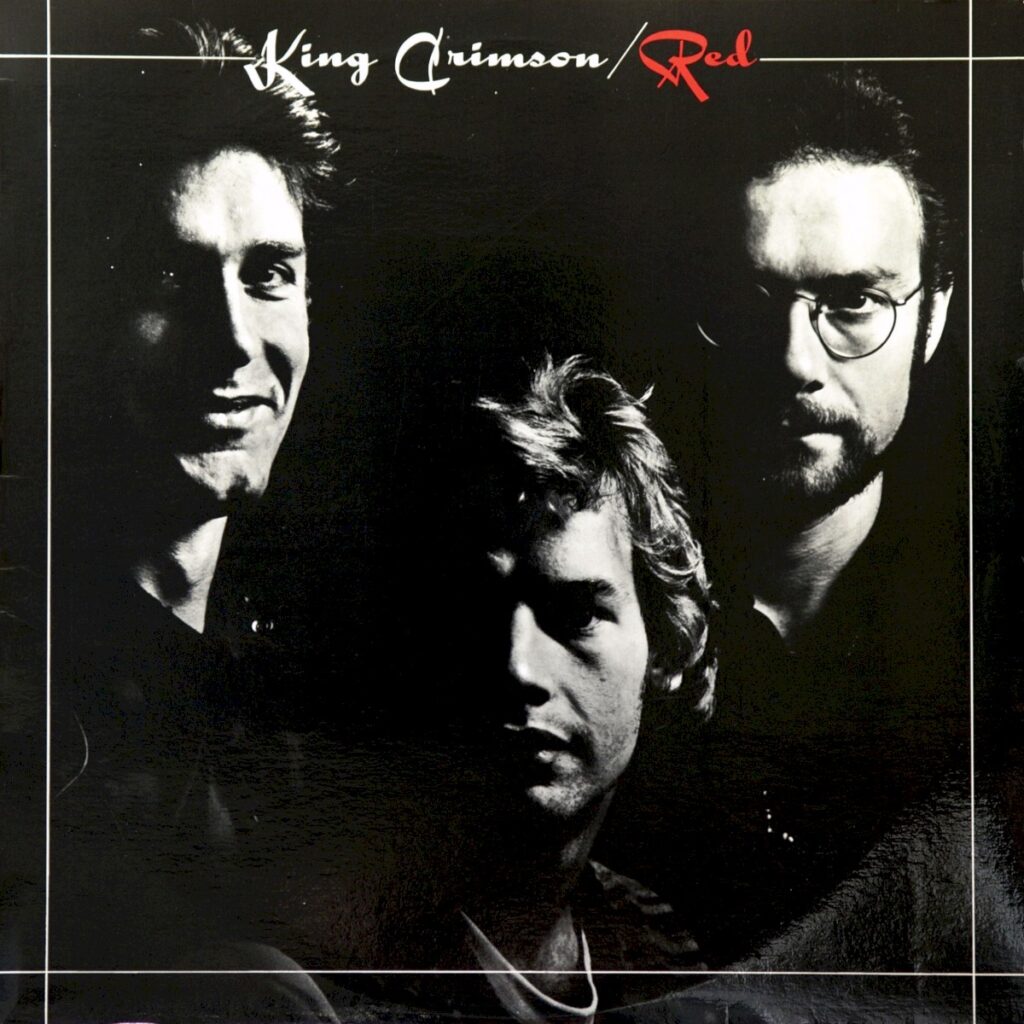

King Crimson, ‘Red,’ 1974

Did you ever anticipate such brilliance from an album birthed as the band neared its end? From the outset, everyone in King Crimson knew Red would be their final bow. Robert Fripp was stepping away from the music world, and the palpable tension among the members had already driven David Cross to limit his contribution to a single track, his violin parts curtailed from their expansive live renditions.

Yet, in the twilight of their journey, something extraordinary transpired. Was it a meteor from the heavens, or perhaps a visitation from the fiery depths of the cosmos? Robert Fripp, ever the cryptic maestro, only hints at a presence felt on the last night of their 1974 US tour—the Crimson King itself. When this entity descends and channels through Fripp, the band ascends to superhuman heights. Red stands as a litmus test. While In the Court of the Crimson King may be more celebrated, true aficionados proclaim Red as King Crimson’s magnum opus, a towering achievement in the annals of music. It’s a masterpiece that unfolds gradually, with some elements captivating instantly, while others reveal their depth over the years. Consider the intricate dynamics of ‘Starless’ or the immediate perfection of ‘Providence.’

The album, clocking in at just over 30 minutes of new material, is rounded out by an improvisation captured at the Palace Theatre in Providence, Rhode Island, on the eve of their final tour night in 1974. This improvisation, unlike King Crimson’s usual context-dependent pieces, stands alone as a testament to their genius. While Fripp’s compilations of improvisations often falter, Providence shines as a modern classical marvel, a rare feat even among the greats of jazz and improvisation. No rock band had dared tread this path before King Crimson, and it often takes years for fans to fully appreciate its brilliance. Starless emerges as one of the most significant compositions of the late 20th century, akin to the works of Penderecki. Unlike the sudden revelation of Providence, Starless is a deliberate exploration of musical boundaries. It begins with a deceptively simple pop tune, only to morph into a postmodern deconstruction in its middle section, challenging our very understanding of music. This section, seemingly repetitive, builds a Hitchcockian tension, crescendoing into a screeching climax. The ensuing chaos, though seemingly random, is meticulously crafted, culminating in a reprise that feels like a ray of hope piercing through the madness. John Wetton’s coda in Starless is a towering achievement, bringing a tragic peace to the controlled chaos.

Wetton’s bass work on Red is nothing short of majestic, roaring through the apocalyptic landscapes conjured by Fripp’s guitars and the haunting cello. Interestingly, an unrecorded counterpart to Red, titled Blue, saw some of its elements woven into Red and later performed with Brian Eno. While the jazz influence on Red is often attributed to the brass, it’s Bill Bruford’s drumming that truly carries the jazz torch. His slightly swinging beat in Fallen Angel could fit seamlessly into a jazz-funk record, adding a unique flair to this melancholic ballad infused with old Hollywood noir and doom metal climaxes. One More Red Nightmare showcases Bruford’s clinical precision, echoing the title track’s riffing.

Released in 1974, Red stands as a defining moment, even among the year’s other monumental rock releases. It’s the heaviest and darkest album from one of Britain’s pioneering heavy metal bands, its influence slowly blossoming in the 1990s. Red paved the way for genres like alternative and post-metal, inspiring bands like Tool, Neurosis, and Nirvana. Many ’90s metal bands may not have fully grasped how much they owed to King Crimson, particularly to Red. The significance of Fripp’s work on this farewell album cannot be overstated. His compositional prowess, innovation, and ability to capture the darkest essence of music are unparalleled. The cover’s shadowy faces mirror the album’s somber tone—a fitting goodbye delivered with fierce intensity.

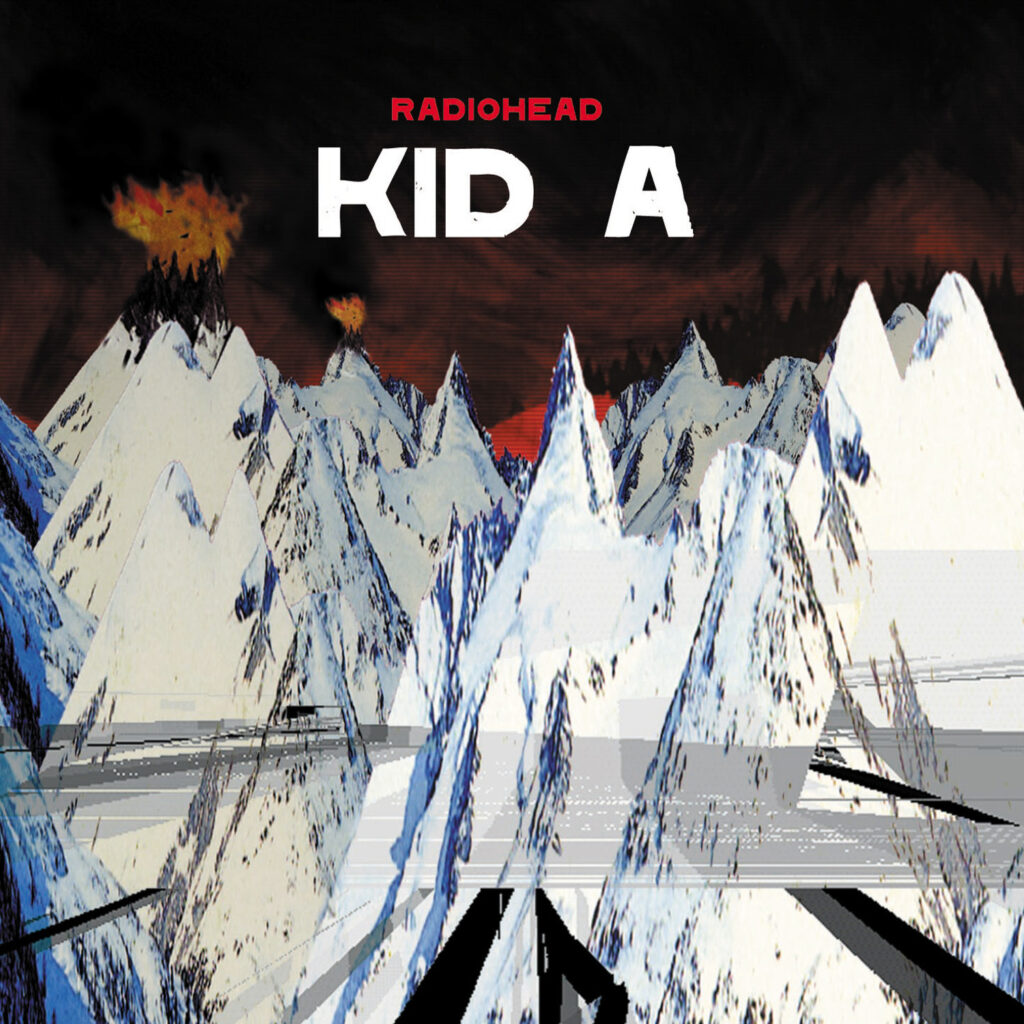

Radiohead, ‘Kid A,’ 2000

“Time will judge it. But right now, Kid A has the ring of a lengthy, over-analysed mistake.” So declared NME upon the release of Radiohead’s feverishly anticipated fourth album. The sentiment was far from unique—critics seemed to stumble over themselves in their haste to dismiss it. The Guardian awarded it a meager two stars; Melody Maker went even lower with 1.5. Yet amid the skepticism, Spin’s 9/10 review stood as a rare beacon of clarity, hailing Kid A as anything but “career suicide” and predicting it would one day be revered as the band’s finest work. Of course, hindsight makes prophets of us all. It’s easy now to smirk at those early takedowns, penned under tight deadlines, grappling with an album that felt, at the time, like an act of deliberate provocation. And yes, some critics did indulge in hyperbolic scorn—but then, moderation has never been what readers demand from their reviewers. By year’s end, many of those same detractors had quietly folded Kid A into their “Best Of” lists. Like fans, critics needed time to let it settle, to absorb its strange, shifting contours.

When Kid A dropped in October 2000, Bill Clinton was president, the Twin Towers were standing, Donald Trump was a washed-up real estate huckster, and the internet still held the promise of educating young minds and uniting mankind. But the 11 tracks Radiohead assembled for their fourth album — utilizing sequencers, drum machines, vintage synthesizers, strings, and a brass section — foresaw a darker 21st century, one marked by fear, loneliness, dislocation, and technological advancements that only divide us further. (In other words, they knew exactly where we were headed.)

The making of Kid A (and its shadow sibling, Amnesiac) was, by all accounts, a trial. Haunted by the specter of their own influence—the glut of Radiohead-lite acts clogging the post-Britpop landscape—Thom Yorke feared stagnation. Guitarist Ed O’Brien’s wish for concise, melodic songs clashed with Yorke’s growing wariness of melody itself. Instead, the band submerged themselves in the electronic abstractions of Warp Records, emerging with something that, while indebted to those sounds, was unmistakably their own. Detractors dismissed it as derivative, but they missed the point: Kid A wasn’t an imitation—it was a reinvention, infused with jazz, hip-hop, Krautrock, and even the ghostly pulse of Remain in Light.

The critics who panned Kid A must have felt, in time, the same sting as those who lavished perfect scores upon Be Here Now. That Oasis album blazed brightly on first listen before crumbling like a sugar-rush hallucination. Kid A worked in reverse. It wasn’t just an album to hear—it was a world to inhabit. I’d lose myself in its icy, alien soundscapes, pacing the same frozen tundra depicted on its cover. With each visit, the cold receded, revealing something luminous, almost tender beneath. Only those who clung to the idea of Radiohead as a “guitar band” remained shut out, their frustration hardening into a permanent grudge against experimentation itself. Though no singles were released, Kid A’s songs seeped into the cultural bloodstream all the same. The queasy euphoria of Everything in Its Right Place, the chaotic jazz-throb of The National Anthem, the glitchy, apocalyptic thrum of Idioteque—these became anthems in their own right, their power undimmed by repetition. Yet the album’s true magic lies in its quieter moments. Treefingers, dismissed by some as ambient filler, is a breath of crystalline calm after the devastating How to Disappear Completely. The title track, with its eerie, childlike warble, feels like stumbling upon some half-forgotten nursery rhyme from another dimension.

The Kid A sessions nearly tore the band apart. But what emerged was not just an album, but a rebirth. The critics who called it a misstep soon recanted; by decade’s end, it topped countless “Best Of” lists, its legacy secure. There’s a quiet triumph in that—a story of slow-dawning recognition as rewarding as the music itself. Kid A is an album that refuses to fade, revealing new depths with every listen. It wasn’t a mistake. It was a revelation.