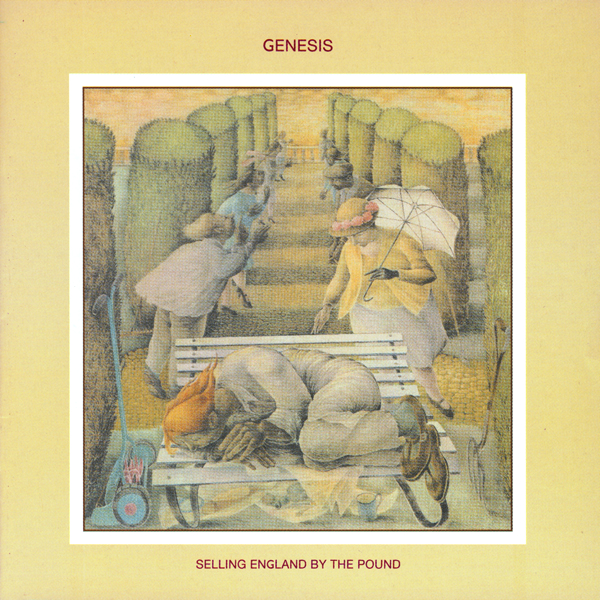

Genesis, ‘Selling England by the Pound,’ 1973

Now as the river dissolves in sea

So Neptune has claimed another soul

And so with gods and men

The sheep remain inside their pen

Until the shepherd leads his flock away

The sands of time were eroded by

the river of constant change

It begins without any music, with Peter Gabriel’s voice asking “Can you tell me where my country lies?” This question hangs in the air, both intimate and profound—a perfect introduction to an album that serves as the reply to that very inquiry. The answer, while musically mind-blowing, offers little comfort for the soul of a nation. Selling England by the Pound functions as something of a concept album, though not in the traditional sense where songs explicitly connect. Instead, a recurring musical motif found in Dancing with the Moonlit Knight and the closing tracks subtly binds this tapestry together. Genesis excels at lyrical storytelling, often employing different characters to illuminate real life in ways that perfectly complement their symphonic progressive approach.

Dancing with the Moonlit Knight opens the album with Gabriel’s haunting a cappella invitation before evolving through gentle acoustic and piano passages into a lively, almost frenetic middle section. It builds to one of Genesis’ hardest-rocking moments before easing into a beautifully reflective conclusion. The lyrics paint England in decay, offering listeners a chance to “dance with the moonlit knight” and defy the trends destroying their cultural identity. The album’s genius lies partly in its structure—shorter pieces interweaving with epic compositions, creating perfect flow. I Know What I Like (In Your Wardrobe) follows as a shorter, less serious song based on the album’s cover art. Sung from the perspective of a lawn mower, it carries a trippy, almost psychedelic quality with interesting flute passages and that infectious “I know what I like and I like what I know” vocal hook. Though cryptic and occasionally laugh-inducing, it never feels immature—just gloriously, peculiarly English.

Firth of Fifth stands as a progressive masterpiece, beginning with Tony Banks’ virtuosic keyboard overture that shifts through constantly changing meters. The piano work remains impeccable throughout, eventually giving way to a creamy, flowing guitar solo that melts into the sonic landscape. Even with its extended instrumental passages, it remains wonderfully listenable—pure prog in its finest form. More Fool Me offers a gentle respite between the album’s longer compositions. While it doesn’t quite reach the heights of surrounding tracks, its emotional vocal work and understated accompaniment provide necessary breathing space without disrupting the album’s flow.

Then arrives the album’s most ambitious piece, The Battle of Epping Forest. This epic depicts a territorial gang war as a bizarre public spectacle, beginning with a drum march mixed with keyboards before launching into its main theme. Gabriel adopts various character voices throughout—sometimes disconcertingly—as he portrays the absurdity of violence-as-entertainment. Despite its occasional tedium, the song maintains an unsettlingly upbeat tone as onlookers picnic and watch the carnage without intervention. The battle’s conclusion reveals the ultimate futility: every combatant dead, with the winner determined by a coin toss that could have prevented the bloodshed entirely. War, Genesis tells us, is pointless.

The Cinema Show emerges as one of the album’s standout moments, opening with lyrics comparing a woman concerned with appearance and a man’s attempt at seduction before blossoming into some of Genesis’ most sophisticated instrumental work. The track flows magnificently into a reprise of the Dancing with the Moonlit Knigh motif, creating a circular connection that strengthens the album’s conceptual structure. Finally, Aisle of Plenty completes the cycle, depicting a confused shopper while reprising the album’s opening themes. As the music fades, salesmen drone about their products in monotone voices—a final commentary on commercialism’s soul-crushing effect on English society. The album closes with the whispered words “it’s scrambled eggs,” a cryptic yet somehow fitting conclusion to this progressive masterpiece.

Perhaps most importantly, Selling England by the Pound answers Gabriel’s opening question with a profound musical statement: England lies within these notes and words—complex, beautiful, troubled, and ultimately worth fighting to preserve. The moonlit knight still dances, inviting us to join in defiance of the forces that would reduce a nation’s soul to items on a supermarket shelf.

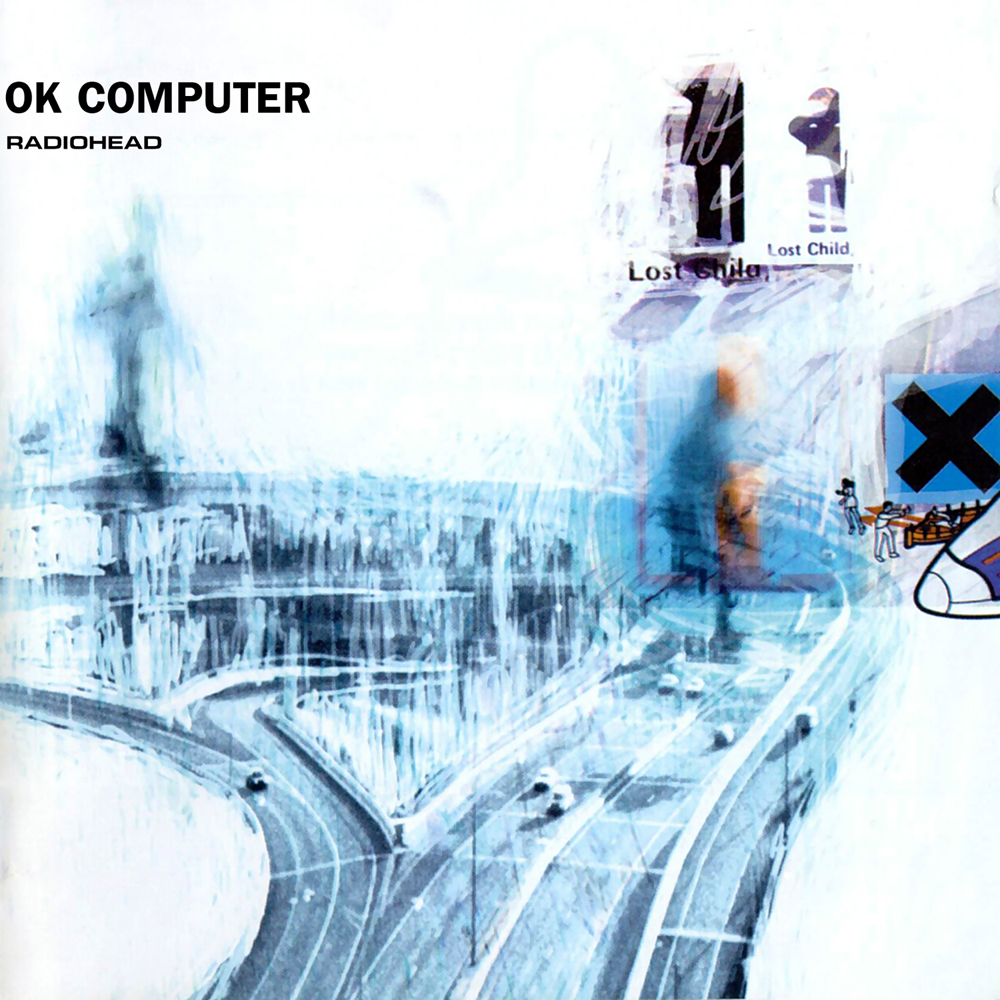

Radiohead, ‘OK Computer,’ 1997

OK Computer is a haunting, prophetic meditation on late-90s society—an album that balances its political weight with breathtaking artistry, making it not only listenable but transcendent. It is a rare masterpiece, one that oscillates between dystopian dread and fragile beauty, cementing itself as one of the greatest albums ever made. While tracks like Airbag and Paranoid Android delve into Thom Yorke’s personal psyche, songs such as Karma Police, No Surprises, and Fitter Happier paint a broader, unsettling portrait of societal decay. Yet, amid the disillusionment, there’s an undercurrent of yearning—for connection, for peace, for a world untainted by external forces. OK Computer is Radiohead’s magnum opus, a work of staggering depth and vision.

The journey begins with Airbag, its jagged guitars and propulsive drums mimicking the sudden jolt of survival—a rebirth after a near-fatal crash. Yorke’s lyrics, cryptic yet vivid (“In an interstellar burst / I am back to save the universe”), mirror the song’s celestial guitar work, as if the music itself is a burst of light in the void. Then comes Paranoid Android, a shapeshifting epic that glitches between fury and melancholy. Its futuristic sheen and fractured structure—like a malfunctioning AI’s lament—build toward an ethereal climax, dissolving into something almost holy. The song is a fever dream, a barroom encounter refracted through layers of distortion and despair. Subterranean Homesick Alien drifts like a sigh, a plea for escape from a world that misunderstands him. The instrumentation is otherworldly—twinkling, dissonant, as if the guitars are transmissions from some distant galaxy. The drums crash like meteorites, grounding the song’s cosmic longing in raw, human ache.

But nothing prepares you for Exit Music (For a Film). It begins in hushed intimacy, Yorke’s whisper curling around an acoustic guitar, before erupting into a cataclysm of distortion and pounding drums. That first hi-hat hit is a gunshot to the heart—the moment the song detonates into pure catharsis. It is a masterpiece within a masterpiece, a crescendo so devastating it feels like the end of the world. Let Down, though overshadowed, is still radiant—a shimmering ode to collapse. Its harmonies lift and crumble like a body giving way to gravity, the tambourine and guitars intertwining in a delicate dance of exhaustion and fleeting hope. Karma Police is an eerie lullaby, its piano line circling like a predator. The lyrics—part indictment, part paranoid fantasy—capture the suffocating weight of modern judgment, where minor transgressions warrant exile. The way Yorke hisses “This is what you get” feels less like a threat and more like a lament.

Fitter Happier is the album’s cold, mechanical heart—a robotic recitation of hollow self-improvement mantras. The sterile voice, paired with dissonant piano, evokes Orwellian dread, revealing how easily humanity can be reduced to bullet points. Electioneering jolts you awake with its snarling guitars, a blunt-force takedown of political theater. It’s the album’s most direct moment, a rallying cry against empty promises, its fury barely contained by the rhythm section’s relentless drive. Climbing Up the Walls is the sound of madness given form. Yorke’s voice, distorted and whispering, slithers into your skull as the guitars screech like frayed nerves. It’s a song that doesn’t just describe paranoia—it becomes it.

No Surprises is deceptively gentle, its music-box melody belying the exhaustion in its lyrics. Yorke’s plea for a “quiet life” feels like surrender, the final sigh of a man crushed by the weight of expectation. Lucky is an underrated gem, its soaring chorus a rare moment of uplift on an album steeped in unease. Yet even here, there’s tension—the protagonist is blessed but haunted, forever waiting for the other shoe to drop. And then, The Tourist—a perfect closer. Its waltzing tempo and languid guitars feel like the world moving in slow motion, until Yorke’s desperate cry—”Hey man, slow down!”—shatters the illusion. The final bell tolls like a funeral knell, a quiet end to an album that screams into the void. OK Computer is more than an album; it’s a mirror held up to our anxieties, our hopes, our collective unraveling. Decades later, it still feels like a warning—and a revelation.