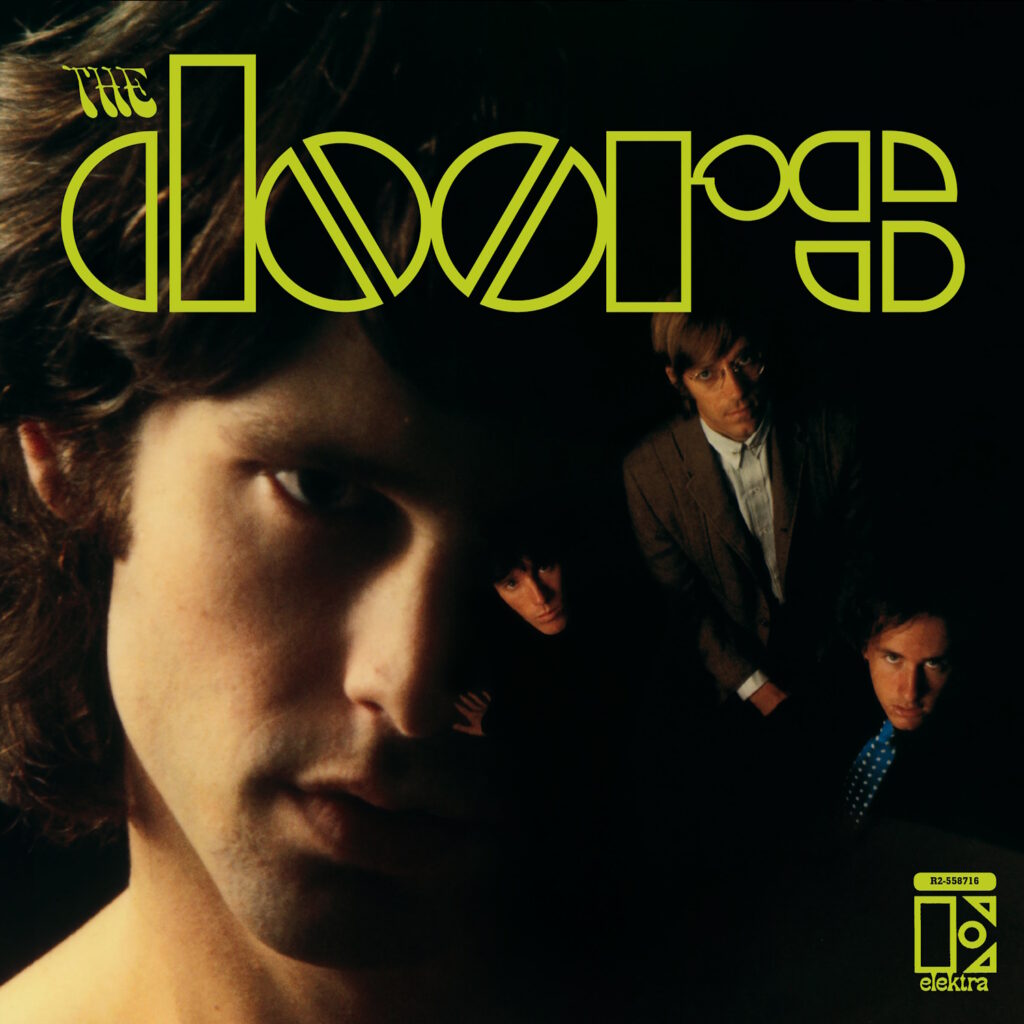

The Doors, ‘The Doors,’ 1967

The world spun on as it always had—wars raged, oil spilled, revolutions simmered—but the true heartbeat of 1967 pulsed in its social and cultural rupture. The year is known for Torrey Canyon, the first oil spill, Mao’s Cultural Revolution massacre, the Vietnam War, Cuba, or the disappearance of Che Guevara, but the definitive fracture created by the impact of the Baby Boomers has changed history forever. They embraced protest, psychedelia, sexual liberation, and spiritual seeking, their voices echoing from Los Angeles to London, from San Francisco to Paris. Tradition crumbled; a new ethos rose.

And with it came a musical revolution. If 1966 laid the groundwork—Pet Sounds, Revolver, Rubber Soul—then 1967 was the explosion. The album, once a commercial afterthought, became an art form. Studios turned into laboratories; artists became alchemists. Boundaries dissolved. Baroque pop, hard rock, free jazz, tropicalia—genres bled into one another, each record a manifesto. And at the heart of it all: The Doors. No band embodied the counterculture’s dark allure like them. Fronted by the incendiary poet-prophet Jim Morrison—a man who wore his torment like a crown—they were a Molotov cocktail of blues, psychedelia, and existential fury. Morrison, a Rimbaud in leather pants, was a storm contained in flesh: brilliant, self-destructive, impossible to ignore. Behind him, Ray Manzarek’s hypnotic organ, Robby Krieger’s serpentine guitar, and John Densmore’s jazz-inflected drums wove a sound both primal and sophisticated.

This was rock & roll stripped bare—raw, dangerous, and drenched in poetry. Morrison’s demons were forged early. A Navy brat, rootless and solitary, he witnessed death at four—a pile of Native American bodies on the roadside—a trauma that haunted his art. Literature became his refuge; philosophy, his weapon. By 20, he was adrift in Venice Beach’s bohemia, a dropout scribbling verses in dim-lit cafés. Then came the music. The band’s formation was fate’s rough draft. Manzarek, the classically trained keyboardist, met Morrison at UCLA. Krieger and Densmore, jazz and blues acolytes, completed the quartet. They played dive bars, Morrison slurring lyrics between tequila shots, the crowd unsure whether to cheer or flee. Then came The End—a Oedipal scream that got them banned, then infamous, then signed.

Recorded in a week, The Doors arrived like a Molotov through a stained-glass window. No singles, no concessions—just art, uncompromising. Break On Through (To The Other Side) is the perfect overture: Morrison’s voice, equal parts seduction and snarl, rides Krieger’s jagged riff and Manzarek’s spiraling organ. It’s proto-punk, psychedelic blues—a manifesto in under three minutes. Then, the swing of Soul Kitchen, a love letter to late-night diners and the misfits who haunt them. The Crystal Ship follows, a baroque ballad where Morrison plays the doomed crooner, his words veiled in opium-dream imagery. And then—Light My Fire. Seven minutes of transcendence. The verses smolder; the instrumental break ignites. Krieger’s flamenco-tinged solo, Manzarek’s hypnotic organ—it’s a rite of passage, a summoning. By the time Morrison returns, howling “The time to hesitate is through!”, the song has seared itself into history. Even the covers—Brecht’s Alabama Song, Howlin’ Wolf’s Back Door Man—feel like Doors originals, reshaped in their own infernal image.

And then, the finale: The End. Eleven minutes of dread and catharsis. Morrison whispers, then roars, then unravels entirely. “Father? Yes, son. I want to kill you.” It’s theater, it’s psychosis, it’s genius. By the last echoing note, you’re left breathless—changed. Few debuts have ever felt so fully formed. The Doors is a fever dream, a séance, a reckoning. It’s Morrison’s cursed poetry set to flame, his bandmates weaving spells around him. It’s also timeless. Listen now, and Break On Through still feels dangerous. Light My Fire still hypnotizes. The End still chills. The world tried to tame Jim Morrison. It failed. He burned too bright, too fast—but the door he kicked open? It never closed.

The Jimi Hendrix Experience, ‘Electric Ladyland,’ 1968

The Jimi Hendrix Experience may have burned briefly—just four years and three albums—but they transformed each moment into sonic revelation, each release pushing further beyond known boundaries. Their final testament, a power trio’s swan song, delivered one of the late 60s’ most enduring musical tapestries. While Hendrix’s transcendent guitar work, Noel Redding’s foundational bass, and Mitch Mitchell’s rhythmic alchemy formed the core, Electric Ladyland expanded into a celestial gathering of eleven additional musicians who contributed flute, saxophone, Hammond organ, piano, 12-string guitar, congas, and vocal harmonies—creating the most expansive and expensive soundscape of their brief but blinding career.

The Experience continued their cosmic trajectory, weaving psychedelic blues-rock that seamlessly flowed between hard rock intensity, blues soul-searching, and funk grooves kissed by jazz improvisation. Hendrix himself, possessed by creative fever and perfectionism, spent countless hours in meticulous pursuit of aural perfection—recording, reimagining, and polishing each passage until it gleamed with otherworldly brilliance. The track Gypsy Eyes alone demanded 50 takes across three exhaustive sessions. Yet despite this painstaking construction, Electric Ladyland paradoxically flows like a spontaneous cosmic jam, a river of sound carrying listeners from source to sea with natural, inevitable momentum.

Hendrix’s creative wellspring ran so deep that a single album couldn’t contain it. At over 75 minutes, this double album asked listeners for committed immersion—a request they eagerly granted as it ascended to chart supremacy. Their reimagining of Dylan’s All Along The Watchtower gave the Experience their sole American Top 40 hit—a version so definitive that Dylan himself acknowledged its transcendence of his original. While the public embraced this ambitious sonic journey, critics initially struggled to contextualize its kaleidoscopic vision. Time, however, revealed what audiences intuitively understood: Electric Ladyland had effortlessly united disparate musical languages—funk’s physicality, blues’ emotional depths, rock’s raw power, jazz’s sophisticated freedom, and psychedelia’s cosmic awareness—into a singular, unified statement now rightfully enshrined among rock’s greatest achievements.

The album crafted a richer, more intricate musical architecture than its predecessors Are You Experienced? or Axis: Bold As Love. Though still anchored in the blues-infused heavy rock and virtuosic guitar exploration that had catapulted Hendrix to fame, Electric Ladyland transcended rock’s perceived limitations. Like The Beatles’ paradigm-shifting Sgt. Pepper’s the year before, it pioneered experimental techniques—backmasking, chorus effects, echo chambers, and flange—that expanded recording’s possibilities. The sprawling 15-minute Voodoo Chile anticipated progressive rock’s formal revolution, prefiguring the seismic shift King Crimson would complete with In The Court Of The Crimson King the following year. Hendrix had crafted that rarest of musical achievements: an album accessible enough to captivate the masses yet layered with enough mystery to reward endless exploration.

Within this eclectic tapestry, Hendrix showcased his multifaceted artistic vision. Voodoo Chile channels the deepest currents of blues tradition, while Come On pulses with R&B’s rhythmic heartbeat, and Crosstown Traffic blazes with acid rock’s incandescent energy. Little Miss Strange, with Mitchell’s rare lead vocal turn, introduces a curious 60s beat pop interlude amid the psychedelic maelstrom—all these disparate elements unified by Hendrix’s cosmic perspective. One senses that Hendrix approached this album as his magnum opus, his attention to detail revealing a visionary who labored relentlessly at his sonic canvas. The prophetic message in the album’s closer Voodoo Child (Slight Return)—”If I don’t meet you no more in this world, then I’ll meet you in the next one, and don’t be late”—haunts us with the possibility that Hendrix somehow sensed his haunts us with the possibility that Hendrix somehow sensed his earthly journey would be brief, making this masterwork all the more precious. Rather than transcending its era, Electric Ladyland instead serves as a portal—a shimmering gateway that transports modern listeners back to experience the purest essence of what made that revolutionary period so transformative. Through Hendrix’s visionary soundscapes, we don’t just remember the late ’60s—we briefly inhabit them, experiencing their most elevated possibilities through the eyes and ears of one of music’s true seers.