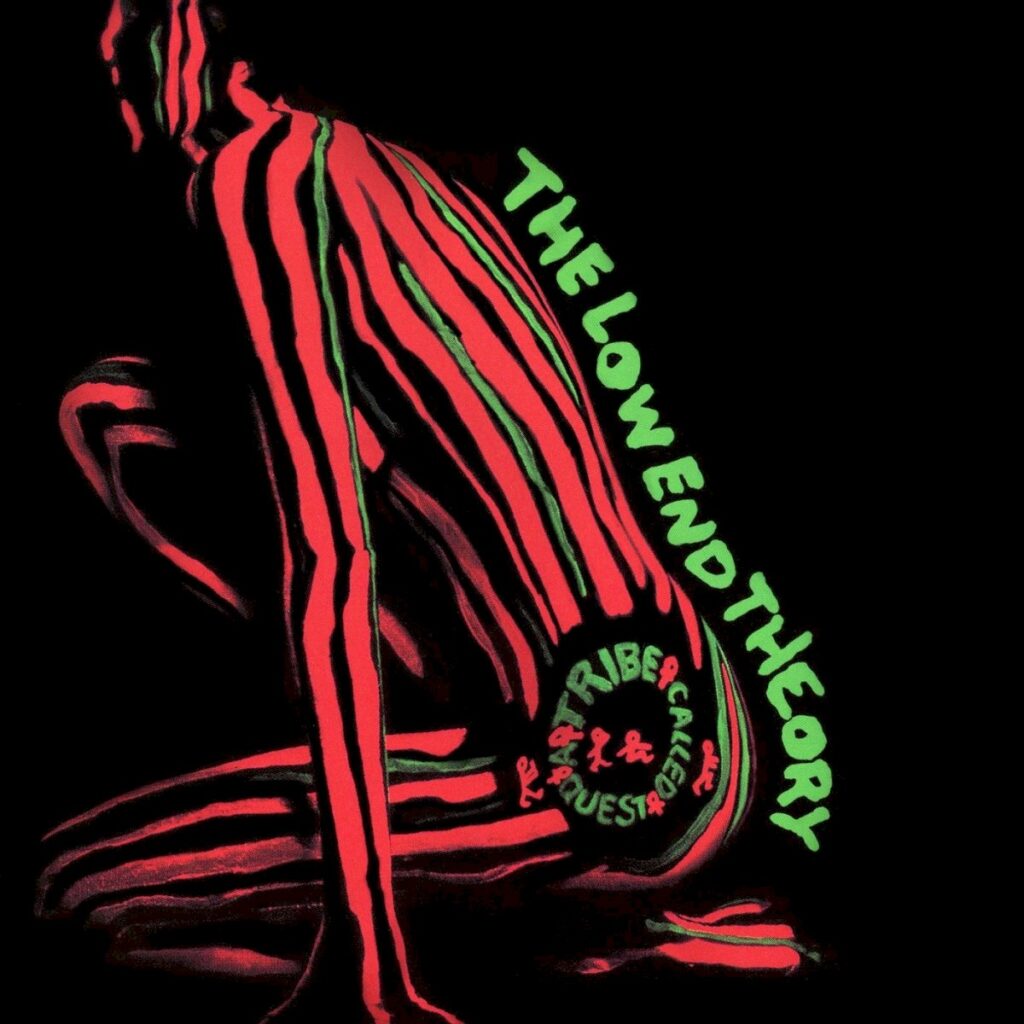

A Tribe Called Quest, ‘The Low End Theory,’ 1991

A Tribe Called Quest’s sophomore album, The Low End Theory, heralded a transformative moment in hip-hop, melding jazz influences and socially conscious lyrics with minimalist, innovative production. The title The Low End Theory encapsulates the duality of both its sonic and social implications. According to group member Phife Dawg, the title refers to the album’s gritty low-frequency basslines as well as a commentary on the low status of Black men in society. This notion is further elaborated by Q-Tip, who portrayed the album as a jazz-inspired outlook on life, advocating for improvisation and innovation against societal odds. A major thematic element of the album is its exploration of everyday life and struggles. While A Tribe Called Quest’s contemporaries often veered towards more mystical or fantastical narratives, The Low End Theory presents on-the-ground accounts of life as young Black men in Queens, New York. This grounded approach gave voice to the marginalized and illuminated the real issues faced by urban youth, encapsulating a form of social commentary that remains relevant decades later. Throughout the album, Phife Dawg’s expanded presence and Q-Tip’s sharp lyricism create a dynamic interplay unique to hip-hop. Phife Dawg, who became more involved in the studio during the recording of this album, delivers lines with a newfound confidence and precision. Q-Tip complements this with his nasal yet mellow flow, each verse intertwined with wit and philosophical musings. The album goes beyond simple wordplay; it delves into topics ranging from relationships and consumerism to the music industry and societal injustices. Tracks like Show Business, where Q-Tip coins the term “Industry Rule #4080” addressing the deceit in the music industry, and Infamous Date Rape, which, although criticized retrospectively, aimed to spark discussion on serious social issues, showcase the breadth of the album’s thematic exploration.

At the heart of The Low End Theory lies its groundbreaking production, credited to the collective efforts of Q-Tip, Ali Shaheed Muhammad, and Skeff Anselm. The production philosophy embraced a minimalist, bass-heavy aesthetic that revered the lower frequencies over the then-popular treble-centric beats. The album’s compositions are a testament to the potential of hip-hop as an art form. Combining jazz samples with intricate drum patterns, the album creates a laid-back yet compelling soundscape. The use of live bass played by jazz legend Ron Carter on tracks like Verses From the Abstract underscores the meticulous attention to sonic detail. A notable feature of the album is its sampling technique. Unlike many contemporaneous records that employed repetitive loops, The Low End Theory comprises elaborate musical constructions from various sources. For instance, Excursions demonstrates this by re-contextualizing a bass-line from Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers into a 4/4 time signature, showcasing the creative ingenuity at play. The Low End Theory‘s profound impact on hip-hop both past and present, its enduring legacy, and its sophisticated execution make it one of the genre’s cornerstones. The album’s seamless fusion of jazz-inflected beats, and socially conscious lyrics inspire artists like Dr. Dre, Kanye West, and Kendrick Lamar.

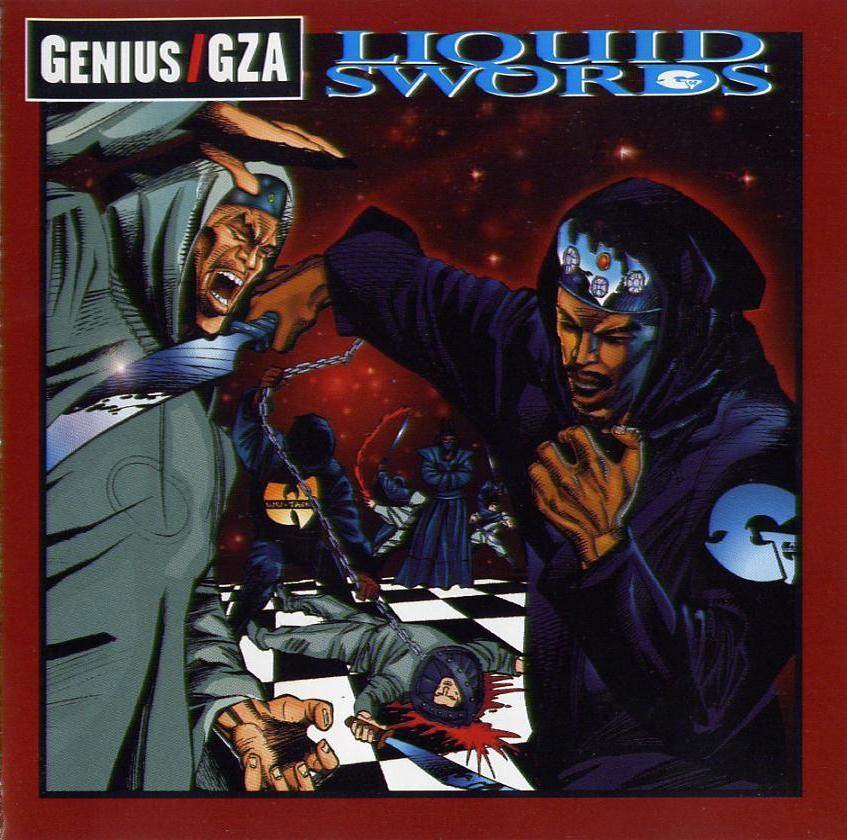

GZA, ‘Liquid Swords,’ 1995

As the second solo studio album from Wu-Tang Clan member GZA, Liquid Swords effortlessly bridges the gap between raw street narratives and cerebral lyricism, underpinned by some of the most atmospheric productions in rap history. Liquid Swords is laden with a dark, brooding vibration that is consistent throughout its runtime. The album draws heavily from Japanese martial arts films, particularly the 1980 movie Shogun Assassin, with numerous samples used to establish a visceral, cinematic feel. The title itself is a direct reference to the kung fu film “Legend of the Liquid Sword,” embodying the idea of being “lyrically sharp with the tongue.” The use of martial arts philosophy is not a superficial add-on but serves as a deep-seated narrative driving the album’s conceptual framework. GZA employs these allusions to frame himself as a modern-day samurai, navigating the treacherous waters of the hip-hop industry and laying waste to lesser MCs with his razor-sharp lyricism. In terms of thematic content, Liquid Swords explores various complex themes including urban life, social injustice, crime, and philosophical reflections. Tracks like Cold World address inner-city despair and systemic issues, while Labels serves as a critique of the exploitative music industry. GZA shines as a master storyteller and wordsmith. His verses are replete with layered metaphors, similes, and a sophisticated wordplay that rewards repeated listens. Particularly notable is GZA’s ability to blend raw street narratives with intellectual undertones. 4th Chamber and Shadowboxin’ feature dense verses from GZA and contributions from fellow Wu-Tang members that tackle topics from philosophical musings to social critiques. Tracks like B.I.B.L.E. (Basic Instructions Before Leaving Earth) are exemplary of the album’s educational aspect, utilizing clever wordplay to delve into deeper existential questions. RZA’s production on Liquid Swords is nothing short of phenomenal and is arguably some of his best work. The album’s composition includes a variety of instrumental and vocal layers designed to enhance the thematic elements. GZA’s beats on the album are both grimy and hypnotic, characterized by a minimalistic yet profoundly atmospheric approach. The beats range from eerie to aggressive, characterized by haunting strings, neck-snapping snares, and deep bass lines. Tracks like track Cold World employ haunting melodies intertwined with skeletal drum patterns to evoke a sense of bleakness and desolation, perfectly complementing the lyrical content. Also, the innovative use of samples from “Shogun Assassin” adds a unique narrative depth and continuity to the album. These samples, which include snippets of dialogue and sound effects from the film, contribute to the album’s dark, cinematic quality.

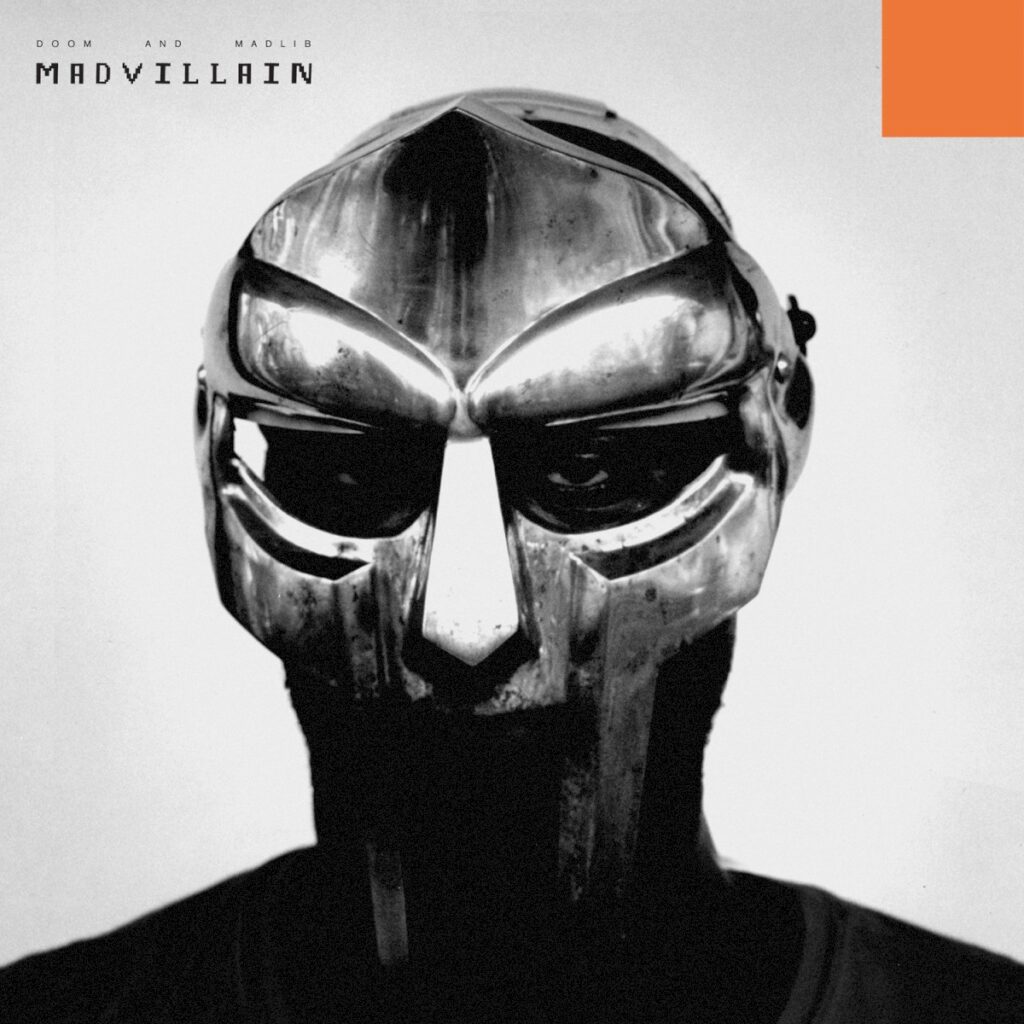

Madvillain, ‘Madvillainy,’ 2004

The only album of the collaborative genius of MF Doom and Madlib, Madvillainy, stands as a conceptually rich and sonically innovative project that has left an indelible mark on the genre as well as my favorite hip-hop album of all time. The concept of Madvillainy revolves around two symbiotic villains residing in the fantastical “Madvillain Bistro Bed and Breakfast Bar and Grill Café Lounge on the Water.” These characters, portrayed by MF Doom and Madlib, are depicted as outlaws with supernatural abilities, embodying the darker sides of human nature. The narrative primarily unfolds through third-person stories and egotistical lines, presenting MF DOOM as a supervillain. Intriguingly, DOOM’s egotistical and nefarious raps are not expressions of arrogance but rather a means to depict the character of a villain. This imaginative setting provides a narrative framework that intertwines the album’s songs, creating a cohesive and immersive listening experience. Thematically, Madvillainy explores the dualities of good and evil, reality and fantasy, and order and chaos. The album delves into the psychology of villainy, presenting its protagonists as complex, multifaceted individuals. Madvillainy is lyrically dense and refreshingly unconventional, as MF DOOM employs third-person narration more often than first-person, infusing his rhymes with a storybook quality. For example, in Accordion, he masterfully juxtaposes banal and bizarre imagery, creating vivid portraits of chaotic urban life. His lyrics often explore themes of deception, self-mockery, and the darker sides of human nature, as seen in tracks like Meat Grinder and Great Day. Navigating through the album, listeners encounter eccentric jokes, cultural references, and wordplay layered with intricate metaphors and allusions. The lyrics remain one of the album’s strongest assets, showcasing DOOM’s prowess as an MC capable of blending humor with profound commentary on society.

Madlib’s production on Madvillainy is a masterclass in sonic experimentation. The album’s soundscape is characterized by its eclectic sampling, lo-fi aesthetics, and unconventional arrangements. Madlib masterfully blends jazz, funk, and psychedelic rock with hip-hop, taking samples from various genres and even old television programs and films. These samples are meticulously chosen to enhance the narrative and character elements of the album. For instance, Raid samples Bill Evans’ rendition of Nardis, adding a jazz-infused texture that deepens the track’s complexity. One of the distinctive features of Madlib’s production is the “drunk” or staggered feel of the beats. Tracks like Accordion embody this style, where the off-kilter rhythms and unconventional timing create a sense of disorientation, mirroring the album’s chaotic themes. This composition style lends the album a distinctively idiosyncratic feel, setting it apart from contemporaneous hip-hop releases. The production quality of Madvillainy is deliberately raw and unpolished, eschewing mainstream hip-hop’s glossy, high-fidelity sound for a more intimate and organic aesthetic. This choice enhances the album’s underground ethos and aligns with the lo-fi sensibilities of the early 2000s hip-hop scene. Madlib’s use of vintage equipment and improvised recording techniques contributes to the album’s warm, analog sound. The cracks, pops, and hiss of vinyl records are integral to the album’s texture, evoking a sense of nostalgia and timelessness. This production approach not only complements Doom’s unconventional flow but also reinforces the album’s themes of chaos and unpredictability.