3.

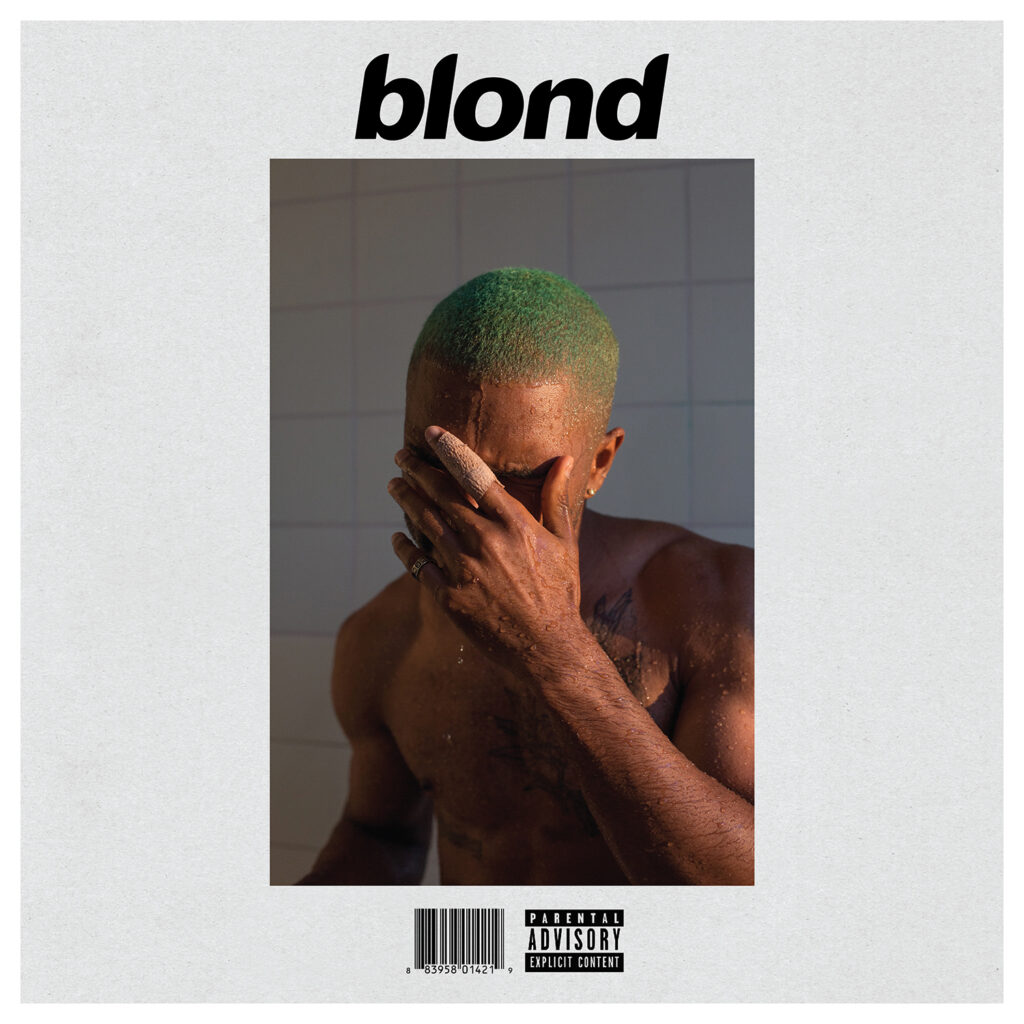

Frank Ocean, ‘Blonde,’ 2016

Back in 2016, no one imagined Frank Ocean would return after four years of silence with an album of minimalist, avant-garde R&B, yet here we are, Blonde in hand. No one could predict what he would return with, or if he would return at all. Blonde is Ocean’s second studio album following 2012’s critically acclaimed Channel Orange. With Blonde, Ocean eschews conventional norms, embracing a minimalist and ethereal approach that challenges genre categorizations, while diving deep into themes of identity, love, sexuality, and emotional complexity. Frank Ocean is the hinge artist of our time, a great storyteller, and the true voice of a generation because he takes long silences.

At the core of Blonde lies the exploration of duality and identity, which is encapsulated in the album’s very title, appearing as “Blond” on the cover and “Blonde” on streaming platforms. This deliberate stylistic choice has been interpreted as a reflection of Ocean’s encounters with both masculinity and femininity, as well as his sexual experiences with different genders. The concept of duality extends further into the album’s narrative, invoking ancient philosophies of non-dualism where contradictions coexist harmoniously. On its surface, Blonde seems tremendously insular. Whereas Channel Orange showed off an expansive eclecticism, this album contracts at nearly every turn. Its spareness suggests a person in a small apartment with only a keyboard and a guitar and thoughts for company. The album’s themes encompass pain, nostalgia, love, and self-discovery, all intertwined with Ocean’s personal anecdotes, philosophical musings, and social commentary in his lyrics. Tracks such as Ivy and White Ferrari explore the shifting dynamics of Ocean’s emotional landscapes, conveying feelings of love, heartbreak, and longing through vivid yet abstract storytelling. The recurring motifs of youth and memory, particularly symbolized by the imagery of blonde hair, further underscore the album’s introspective quality, reflecting on the innocence and carefreeness of Ocean’s younger years, evident in tracks like Nights. Meanwhile, The track Nikes stands out with a delicate examination of materialism, fame, and the commodification of culture, while Solo delves into solitude and the search for self-definition.

Blonde represents a departure from the more polished, radio-friendly sound of Channel Orange. Instead, Blonde is an exemplar of minimalist artistry, characterized by its atmospheric production and genre-defying musicality. The album incorporates a diverse array of styles, including R&B, indie rock, psychedelia, avant-garde soul, and electronica, while employing unconventional musical elements such as pitch-shifted vocals. Ocean collaborated with a host of prolific producers including James Blake, Pharrell Williams, and Malay, alongside notable guest appearances from artists like Beyoncé and André 3000. Throughout the album, many tracks feel empty, with only the plain strumming of an electric guitar or foggy atmospherics left behind, letting Frank Ocean’s voice take center. But they mesmerize. Even a song like Nights, which sounds straightforward at first with its shards of silvery chords and midtempo beat, eventually turns into a strange shredding solo.

The year 2016 crystallized the political disaster right under the surface. People theorized that we needed anthems to get us through the dark night. Big choruses, hooks as wide as highway signs, regular percussion that could gird us from chaos. “Inhale, in hell, there’s heaven,” Ocean sings on Solo, capturing the whiplash experience of being young in this country in one line. Blonde is one synonym for American.

I’m sure we’re taller in another dimension

You say we’re small and not worth the mention

You’re tired of movin’, your body’s achin’

We could vacay, there’s places to go

Clearly this isn’t all that there is

Can’t take what’s been given

But we’re so okay here, we’re doing fine

Primal and naked

You dream of walls that hold us imprisoned

It’s just a skull, least that’s what they call it

And we’re free to roam

2.

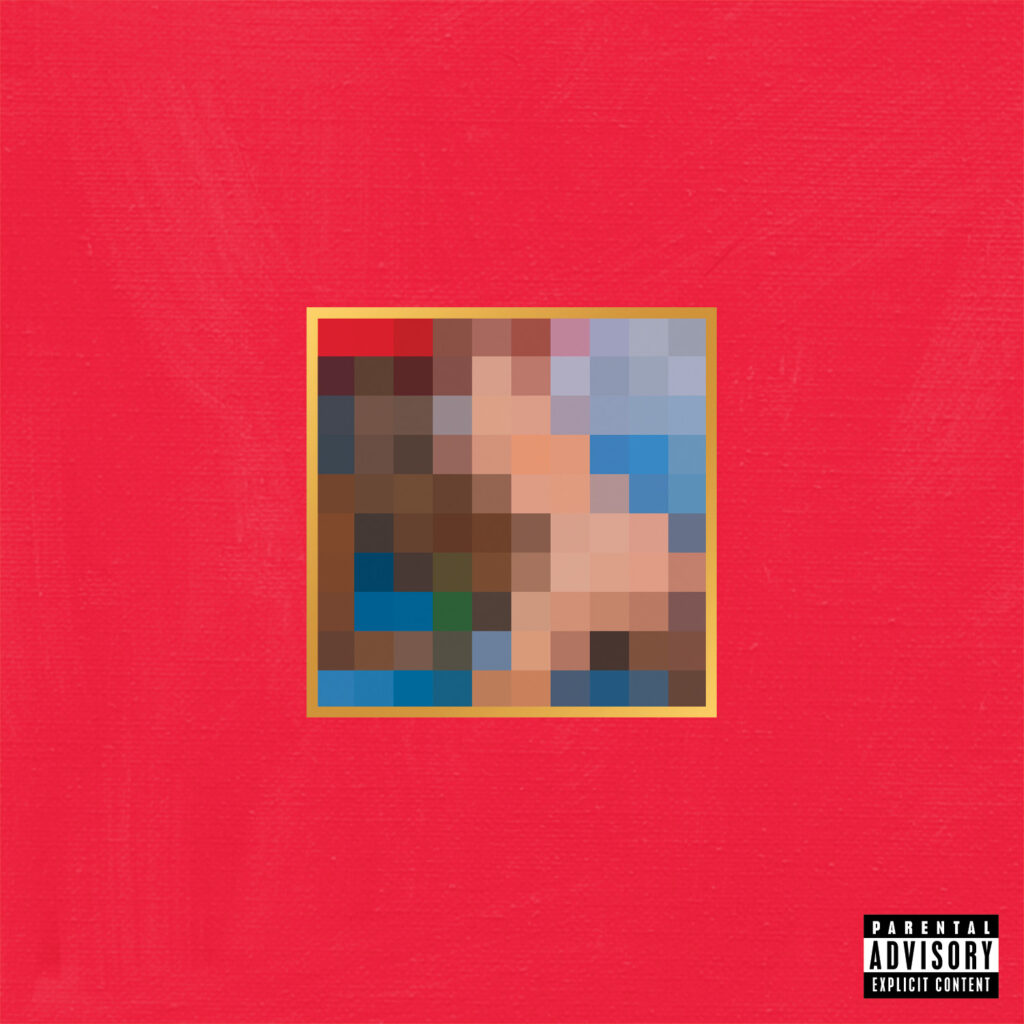

Kanye West, ‘My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy,’ 2010

Hey, teacher, teacher, tell me, how do you respond to students?

And refresh the page and restart the memory?

Re-spark the soul and rebuild the energy?

We stopped the ignorance, we killed the enemy

Sorry for the night demons that still visit me

The plan was to drink until the pain over

But what’s worse, the pain or the hangover?

Kanye West’s fifth studio album, My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy is hands-down the most ambitious mainstream rap album ever made, and the best to be ever produced. In the hip-hop genre and culture, which expects its great artists to submit to a vague set of ideological rules, it is difficult to pinpoint exactly where Kanye West fits into the pantheon of hip-hop royalty. Kanye breaks plenty of rules on MBDTF. The album is composed of nine-minute rap epics that don’t adhere to traditional verse-chorus-verse guidelines. False endings give way to noodling instrumental outros. But perhaps the rule Kanye violates the most flagrantly is also the biggest recipe for disaster: Don’t sound like you are setting out to make the greatest album of all time. Yet he somehow pulls it off.

MBDTF delves into a myriad of themes which include celebrity fame, self-indulgence, materialism, romantic entanglements, and existential musings. It paints a picture of excess and the psychological conflicts experienced by Kanye, as he navigates the pitfalls of fame. Through intricate storytelling and layered lyricism, the album presents West as both protagonist and antagonist, grappling with his ambitions and vulnerabilities. MBDTF is Kanye’s most maniacally inspired music, reflecting a journey through the artist’s psyche where he wrestles with his identity and aspirations. The album also examines the idealism of the American Dream, and whether reaching that zenith is truly fulfilling or fraught with disillusionment. The lyrics of MBDTF are a stronghold of Kanye’s internal dialogue, characterized by self-aggrandizement and moments of raw vulnerability. The album’s centerpiece, Runaway, is Kanye’s most arresting showcase as a songwriter. The self-lacerating lyrics, including a filthy first verse (“She find pictures in my email/I sent this bitch a picture of my dick”), are far too off-putting to count as anti-hero posturing, much less as self-pity. Tracks such as Blame Game and So Appalled find an introspective Kanye reflecting on the trappings of fame and fortune and how they relate to his humanity.

The maximalist aesthetic of MBDTF is notable, with luxurious production that explores symphonic sounds, progressive rock, and soul-infused beats. The complexity of the arrangements and the opulent layerings contribute to the album’s characterization as a “rap opera,” visually and sonically vast in its execution. The album employs samples from obscure prog-rock, indie-folk, and abstract electronica to create a multifaceted auditory experience, such as King Crimson in POWER, Aphex Twin in Blame Game, and Smokey Robinson in Devil In A New Dress. Just as ambitious as All of the Lights, Kanye turns the posse track formula on its head by bringing together Rihanna, Alicia Keys, Elton John, John Legend, Fergie, Kid Cudi, Ryan Leslie, Charlie Wilson, Tony Williams, and Elly Jackson over an epic horn-driven track, but it doesn’t stop there. Nicki Minaj delivers an amazing verse on Monster; A fuzzed-out Raekwon verse is one of the highlights of Gorgeous and nobody can bellow the words “fucking ridiculous” in quite the same way as his Wu-Tang brother RZA on So Appalled. John Legend’s soulful vocals and piano set a nice backdrop to Chris Rock’s jokes on Blame Game. Justin Vernon of Bon Iver lends his voice to both Monster and the frantic album closer Lost in the World. Kanye is the exemplary model of what hip-hop has become and where it is headed, and MBDTF is the game changer.

I just needed time alone, with my own thoughts

Got treasures in my mind but couldn’t open up my own vault

My childlike creativity, purity and honesty

Is honestly being crowded by these grown thoughts

Reality is catching up with me

Taking my inner child, I’m fighting for custody

With these responsibilities that they entrusted me

As I look down at my diamond encrusted piece

1.

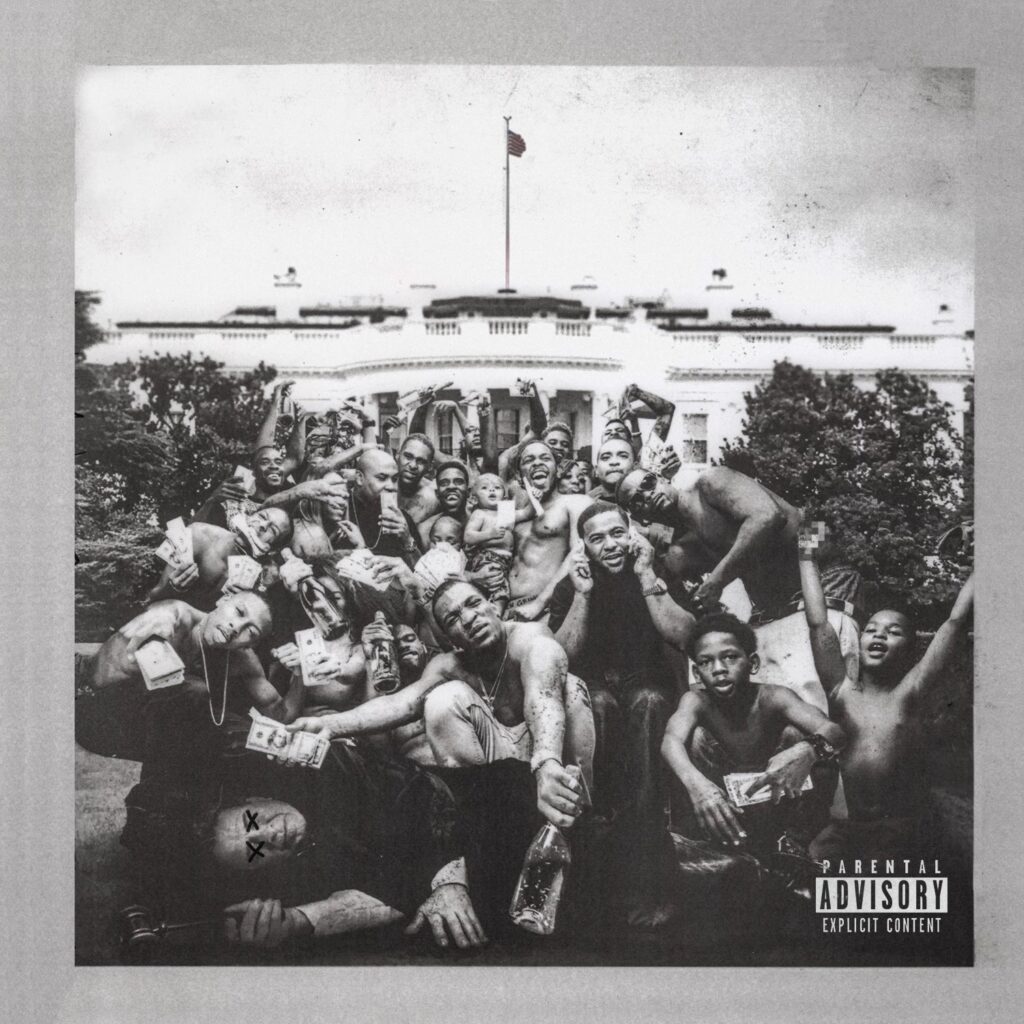

Kendrick Lamar, ‘To Pimp A Butterfly,’ 2015

Walls telling you to listen to Sing About Me

Retaliation is strong, you even dream ’bout me

Killed my homeboy and God spared your life

Dumb criminal got indicted same night

So when you play this song, rewind the first verse

About me abusing my power so you can hurt

About me and her in the shower whenever she horny

About me and her in the after hours of the morning

About her baby daddy currently serving life

Through his 2012 breakthrough, good kid, m.A.A.d city, Kendrick quickly earned his reputation by being an artist with the rarest skill sets: technical mastery, narrative focus, and piercing social consciousness. Lamar took rap back to the streets with a knotty, Joycian account of a man in Compton navigating daily life’s travails. It was an ambitious album that brought Lamar fame but left him conflicted about its cost. The idea of “getting out of the ghetto,” a concept so many rappers strive for, left him with what he terms “survivor’s guilt.” To Pimp a Butterfly was born of this guilt, but it was emboldened by the deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner—by the heightened awareness of what it means to be black in America. The album navigates through a range of themes from self-love and hate, to fame, depression, violence, race, and politics, all intricately woven together through a spoken-word poem that serves as a narrative thread across the album.

In To Pimp a Butterfly, Lamar condemns police brutality and slights Obama; he fears the government, recognizes an institutionalized incentive to ghetto life, and identifies with an 18th-century slave. To Pimp a Butterfly proves to be intensely alive, celebrating humans’ potential for triumph, recognizing how completely things can go awry, and condemning the scars left by American history. Opener Wesley’s Theory immediately establishes the black-power theme by throwing up a sample of Boris Gardiner’s “Every Nigger Is a Star,” and the album ascends through black culture from there. There is nothing as thematically prevalent as Kendrick’s urge for Black Americans to rise above racism, but he’s also enamored with the country as a whole, not to mention his troubles with depression and how his faith in God helps him keep his head above water. The album may not have a definite message, but on the track i and elsewhere, it promotes self-betterment. However, on the track’s frantic companion, the chaotic free jazz excursion u, Kendrick turns a mirror on himself, screaming, “Loving you is complicated!” and suggesting his fame hasn’t helped his loved ones back home.

The excoriating The Blacker the Berry starts out promising to expose himself as “the biggest hypocrite of 2015”, and ends with the confession that, despite his virtuous, politically-conscious stance on many issues and justified anger at police violence, he is still a contributory and culpable player. On For Free? (Interlude) an impatient woman ticks off a laundry list of material demands before Kendrick snaps back that “This dick ain’t free!” and thunders through a history of Black oppression. The album is dotted with surreal grace notes, like a parable: God appears in the guise of a homeless man in How Much a Dollar Cost, and closer Mortal Man ends on a lengthy, unnerving fever-dream interview with the ghost of 2Pac. Complexion (A Zulu Love) is a tender note of appreciation for women of all skin tones with help from North Carolina rapper Rapsody.

To Pimp A Butterfly is an album about tiny quality-of-life improvements to be made in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds. It might not be the message we want in some time where systemic police and judicial inequality have cost many the ultimate price, but that doesn’t bankrupt it of value. Kendrick has a lot to say but willfully obscures his intent perhaps out of the great wisdom of his fallibility, or maybe just because he knows there aren’t any easy answers to the questions he’s asking. To Pimp A Butterfly is a celebration of the audacity to wake up each morning to try to be better, knowing it could all end in a second, for no reason at all.

I seen you from a mile away losin’ focus

And I’m insensitive, and I lack empathy

He looked at me and said, “Your potential is bittersweet”

I looked at him and said, “Every nickel is mines to keep”

He looked at me and said, “Know the truth, it’ll set you free”

You’re lookin’ at the Messiah, the son of Jehova, the higher power

The choir that spoke the word, the Holy Spirit, the nerve

Of Nazareth, and I’ll tell you just how much a dollar cost

The price of having a spot in Heaven, embrace your loss, I am GodI wash my hands, I said my grace, what more do you want from me?

Tears of a clown, guess I’m not all what is meant to be

Shades of grey will never change if I condone

Turn this page, help me change, to right my wrongs